"a scale with a cube of ice on side, white background, white background", image generated with MidJourney

Authors: Muhammad Umair Shah; Umair Rehman; Bidhan Parmar; Inara Ismail

Title: Effects of Moral Violation on Algorithmic Transparency: An Empirical Investigation.

Journal: Journal of Business Ethics (2024) 193:19–34

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05472-3

Publication date: 27 June 2023

Topic: Algorithmic transparency and ethical data collection practices and their impact on users' trust, comfort, and acceptance of algorithms.

Keywords: Algorithmic transparency; Moral violation; Technology ethics

“The age of AI has begun,” stated Bill Gates, demonstrating how it’s reshaping all our activities. And to power this new age, we need data, a lot of data! Just like oil prospectors, companies dig the Web to mine every byte and transform it into valuable services.

ChatGPT developers created its underlying large language model (LLM) by using 300 billion words from the Web (Lammertyn, 2024; Lyer, 2022).

AI algorithms do not use only existing content. They also collect live data from our connected activities and devices at every moment.

From a user perspective, it raises concerns about how it is done and how transparent the process is.

From a company’s point of view, it raises legal and ethical challenges: How can we build trust in our services using algorithms that collect users’ data?

On that topic, Shah et al. (2023) present an article called “Effects of Moral Violation on Algorithmic Transparency: An Empirical Investigation.”

The researchers aim to evaluate how unethical data collection practices, transparency, and perceived acceptability of data-gathering methods influence users’ trust in, comfort with, and acceptance of algorithmic systems.

The title is slightly misleading, as the authors do not discuss the philosophical background of digital morality (Hanna & Kazim, 2021), as expected, but focus specifically on acceptability and transparency in a very pragmatic approach. The abstract adds clarity, giving details about their empirical approach and findings.

Again, the introduction is equivocal, starting with a generic discussion of AI’s impact. However, the study does not really account for AI. It is more about users’ perceptions of transparency design and level of acceptance in collecting data to feed recommendation algorithms that use statistics instead of AI.

The following literature review is exhaustive, fully allowing the reader to understand the author’s rationale and methodological framework. For instance, they define critical concepts like “transparency” as “the right to an explanation” using Goodman & Flaxman (2017) and Springer & Whittaker (2020) and interpret it as “ the ability to understand how an algorithm generates its outputs.”

Their methodology consists of three phases:

a) Define the acceptability of data collection practices

b) Define the notion of interface design transparency

c) Use these definitions to conduct a quantitative survey to understand which factors influence acceptance, comfort, and trust the most.

For all phases but phase 2, they hired participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), which is valid for scientific research, according to Crowston (2012). However, they previously cited Martin (2012), who states that privacy norms and data collection acceptability are context-dependent, which contradicts using AMT.

For phase 2, they used a different approach, hiring 15 undergraduate students through visioconference sessions. The low number of participants and the lack of explanations for this setup change raise reasonable doubts about data relevancy.

Reflections on the study.

For phase 1, they proposed 14 ways to collect information to assess the “acceptability” of data collection practices without mentioning how the list was created. One can question how participants have interpreted the list. For instance, we can find “cookies”–a passive way of collecting data–and “Surveys,” which demand the active participation of users. It is not clear if this influences participant’s answers.

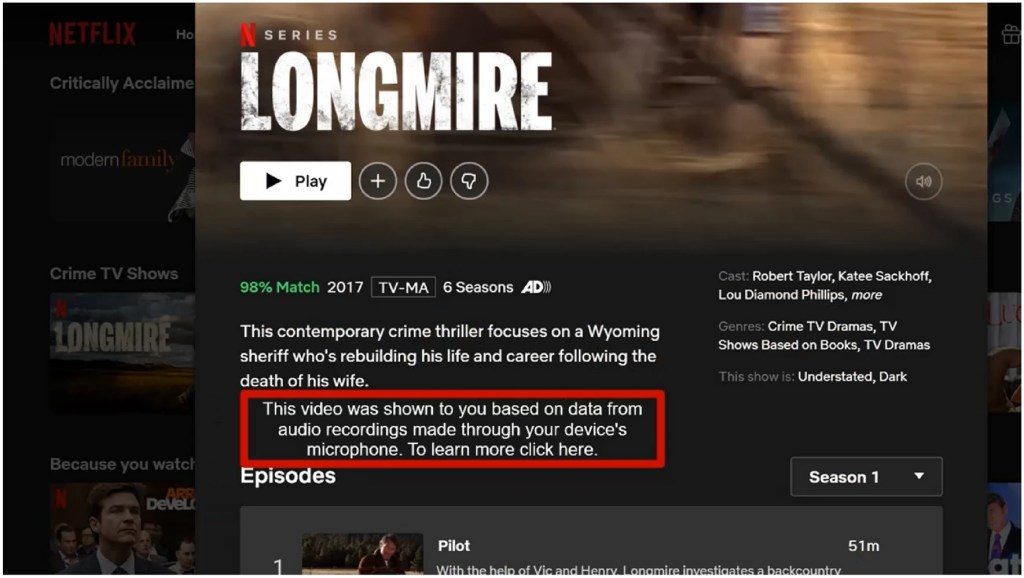

For phase 2, they created short videos to assess “transparency.” The videos simulated Netflix’s home screen. In each video, the access to information about data collection was different: one was hidden in a sub-menu, and the other was visible directly on the home screen.

The difference is caricatural, as the results show that 100% of participants preferred to see the data-collecting practices directly on their home screen. More subtle differences could bring more valuable insights into transparency. All participants showed interest in understanding how their activities are monitored but not by reading lengthy legal documentation, even if easily accessible. It indicates that formatting is an important aspect of transparency, but the authors did not discuss it.

From: Effects of Moral Violation on Algorithmic Transparency: An Empirical Investigation. Fig. 4: "A screenshot of the video showing high transparency with the “audio recordings” data type".

In phases 3 and 4, they used the findings of the previous phases to conduct online surveys with AMT. They employed videos and standardized questionnaires, citing Jian et al. (2000).

Again, the choices presented seemed too distinctive in both phases. For instance, in phase 3, the data collection methods presented to participants were “video recordings of activities,” “files on the device,” “surveys,” and “channels followed,” two very intrusive and two very light methods.

Even if the authors were looking for clear evidence, the methods presented do not really consider more subtle nuances in users’ behavior in the real world, particularly the role of emotions (Patel, 2014; Gray et al., 2018).

They presented their findings using a robust methodology and showed clear, measurable evidence of their hypothesis.

Their results show that algorithm transparency influences trust only when participants perceive data collection practices as acceptable.

When data collection practices are “morally unacceptable,” transparency does not play a significant role.

The article ends by discussing limitations, notably that “(…) different kinds of explanations could alter the results of this study.” It indicates the need for complementary research to understand the factors influencing human trust in algorithms. The authors encourage digital companies to adopt ethical data-collection practices and avoid moral violations.

These findings are of great interest to the field of digital transformation, which heavily relies on data-driven decision-making and AI. The authors contribute to a better understanding of building trust in online services and simultaneously collecting valuable data with fair transparency and acceptability. Finally, the article is an excellent source of references for exploring the link between ethics and digital transformation.

Activities General ISDT Module personal thoughts Reflective practices Search and Social Media Marketing

References:

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for academics: The HIT handbook for social science research. (n.d.). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2016-22118-000

Crowston, K. (2012). Amazon Mechanical Turk: A Research Tool for Organizations and Information Systems Scholars. In IFIP advances in information and communication technology (pp. 210–221). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35142-6_14

Doing Academic Research with Amazon Mechanical Turk - Social Science Matrix. (2024, May 22). Social Science Matrix. https://matrix.berkeley.edu/research-article/doing-academic-research-with-amazon-mechanical-turk/

Gates, B. (2023, March 21). The Age of AI has begun. gatesnotes.com. https://www.gatesnotes.com/The-Age-of-AI-Has-Begun

Gray, C. M., Kou, Y., Battles, B., Hoggatt, J., Toombs, A. L., & Purdue University. (2018). The Dark (Patterns) Side of UX Design. CHI 2018, 1. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3173574.3174108?trk=public_post_comment-text

Hetler, A. H. (2024, July 13). 60+ Facts about chatgpt You Need to Know in 2024. Techtarget. Retrieved August 22, 2024, from https://blog.invgate.com/chatgpt-statistics

Iyer, A. (2022, December 15). Behind ChatGPT’s Wisdom: 300 Bn Words, 570 GB Data. AIM. https://analyticsindiamag.com/ai-origins-evolution/behind-chatgpts-wisdom-300-bn-words-570-gb-data/

Lammertyn, M. (2024, February 8). 60+ Facts about chatgpt You Need to Know in 2024. Invgate. https://blog.invgate.com/chatgpt-statistics

Patel, N. (2014, November 6). How Emotions Affect The Decision-Making Process In Online Sales. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilpatel/2014/11/06/how-emotions-affect-the-decision-making-process-in-online-sales/

Rothman, J. (2024, August 6). In the Age of A.I., What Makes People Unique? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/open-questions/in-the-age-of-ai-what-makes-people-unique

The Age of AI: What exactly is AI? (2022, November 1). Deloitte. https://www.deloitte.com/mt/en/services/consulting/perspectives/mt-age-of-ai-2-what-is-it.html